Each year, during the official Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Day ceremony that takes place at Yad Vashem, six torches, representing the six million Jews, are lit by Holocaust survivors. The personal stories of the torchlighters reflect the central theme chosen by Yad Vashem for Holocaust Remembrance Day. Their individual experiences are portrayed in short films screened during the ceremony.

Here are the stories and photos of the Torchlighters 2025:

Monika Barzel

Monika Barzel was born in 1937 in Berlin. Her father, Eugen, was a doctor, and her mother, Edith, worked as a surgical nurse. Eugen escaped to England, and Edith had to work long hours at the Jewish hospital in Berlin to support the family, so Monika's grandmother, Gertrud, raised her. All three lived in one room in an apartment block in Berlin. Due to her ever-present hunger, most of Monika's early memories focus on food.

When the deportations began in late 1941, Jewish patients whose condition had improved were sent from the hospital to the extermination camps. In an effort to avoid this fate, the doctors and nurses withheld drugs and treatment from the patients, hoping to save their lives. They acted in the full knowledge that, should they be found out, they would be deported along with the patients.

In September 1942, Gertrud was deported to Theresienstadt, where she was murdered. Monika was forced to live with her mother at the hospital, along with the children of four other doctors. From that time until liberation, Monika passed her days at the hospital with no schedule or framework. The nurses and patients were her only friends.

n late February 1943, the Fabrik (Factory) Aktion in Berlin saw the roundup and deportation of Jewish forced laborers to Auschwitz, in order to empty Berlin of Jews. In May, the Gestapo ordered Walter Lustig, the director of the Jewish hospital, to downsize his staff. He was forced to choose 300 people, who were then deported to Auschwitz. Monika boarded the train, but was later told to get off.

Monika contracted diphtheria and other diseases, but she recuperated despite the lack of treatment. She passed an entire winter in her room because she didn't have shoes to wear. From 1944, she spent many nights in shelters due to the bombing of Berlin. She often had to make her way to the shelter alone as her mother was working. From time to time, she slipped on the steep stairs in the darkness and fell into the cellar.

Monika stayed in the hospital until the end of the war. When the Red Army liberated the facility, hundreds of Jews were still alive there. Aware of the murderous and violent tendencies of the Red Army soldiers, the survivors were gripped by fear, even during the liberation period. After liberation, Edith and Monika left Berlin for Sweden and then traveled to London. Edith married Rudi Friedman, a Holocaust survivor from Berlin, and they had a son. Rudy raised Monika as his own daughter.

Monika completed her dentistry studies in London and immigrated to Israel in 1963. She settled in Kibbutz Kfar Hanassi on the Syrian border with her husband, Alan, and found herself back in bomb shelters during the Six-Day War. Monika worked as a dentist in the Upper Galilee, and then around the country—from Kiryat Shmona in the north to Eilat in the south—until she reached the age of 70. Alan succumbed to cancer at age 59. Despite the emotional strain, Monika continued to work and volunteer.

Monika and Alan z"l have two children, six grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

Arie Durst

Arie (Leopold) Durst was born in 1933 in Lwów, Poland (today Ukraine). His brother Marian was born in 1939, the same year Lwów was occupied by the Soviet Union.

In 1941 Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, occupying Lwów. In the wake of the German occupation, many family members came to live with the Dursts. Arie's father was drafted as a doctor in the Red Army. His uncle, Marek Mayer, obtained an essential worker's permit, protecting him from German persecution.

During the Aktionen, Arie and his mother would hide in the potato and coal cellar in the home of Kasia, a non-Jewish woman who had previously been Arie's nanny. Marian, Arie's younger brother, lived under an assumed identity with Marek Mayer, posing as his child since he couldn't be expected to keep quiet in hiding at such a young age.

In one of the Aktionen, Marian Durst was taken and murdered, as were all the members of the Mayer family apart from Marek himself. Arie's mother Salomea obtained forged papers for herself and Arie and arranged to move to Warsaw. She hired the services of a Pole to accompany them, as a mother and son traveling alone would raise suspicion. Once in Warsaw, Salomea rented a room in the apartment of a French widow, who told all inquirers that her tenants were Polish Catholics. Bringing Arie up as a Catholic, the widow took him to church every Sunday and taught him the fundamentals of the Christian faith.

When another tenant had a run-in with the police and policemen came to the building, the doorkeeper managed to delay their entry, and Arie and his mother succeeded in escaping. The Warsaw Uprising broke out the same day, 1 August 1944. Arie and Salomea hid, but they were caught by the Germans after some four weeks and deported to the Pruszków labor camp. Escaping from the moving train, they reached the town of Leśna Góra, where Arie made a living as a peddler until liberation.

At the war's end, Arie and Salomea began their search for Arie's father. They discovered that he had survived the war in the ranks of Anders' Army and was in Tel Aviv. He obtained certificates—entry permits to Eretz Israel (Mandatory Palestine)—for his wife and son, and the family was reunited in 1945. Arie did not know how to read or write, but he started going to school, studied diligently, and eventually joined the academic officers' medical program. He served as a doctor in the Golani brigade of the IDF and was awarded a citation for performing an impromptu operation under fire. He established Israel's first transplant unit and was Head of Surgery at Hadassah Hospital.

Arie inspired the establishment of the Adi organization for organ donation in Israel, and he worked tirelessly to increase awareness regarding the importance of organ donation. He initiated new techniques and procedures in surgery, as well as in the treatment of wounded and cancer patients. He was a senior surgeon and a company commander, and was one of the founders of the IDF medical corps field hospitals.

Arie and Rimona have three children and eight grandchildren.

Gad Fartouk

Gad (Chmayes) Fartouk was born in 1931 in Nabeul, Tunisia, into an observant family of eleven. His father, Joseph, was a member of the community committee, a synagogue benefactor and a textile merchant. Many of his customers were not Jewish, and he maintained a harmonious relationship with them. The Jewish and Arab families in the city customarily celebrated the holidays together. The sellers at the local market knew the family well and would prepare their purchases ahead of time. "We children would just come, pick up the baskets and go home," recalls Gad.

In November 1942, Nazi Germany occupied Tunisia: "We returned from synagogue on Friday night and sat down for dinner. Suddenly there was a knock at the door. Two policemen ordered Father to come to the station," relates Gad. Joseph refused to travel on the Sabbath, so he went on foot to the police station, where he was detained for several hours. The next day, the family moved to Hamam-Lif and lived under assumed identities.

"We didn't go to synagogue anymore, and all our prayers took place at home," recalls Gad. His mother, Ochaya, became ill and died. Joseph remarried, and his second wife Mary "was our mother for all intents and purposes."

When the German presence in the city stepped up, Joseph went into hiding. The Germans would enter the houses, looking for Jews to deport to the camps. Mary sent Gad's two older brothers to hide in the forest. A few days later, Joseph reappeared and took his wife and children to his brother, Basha. Basha lived in Gabès, and was a "protected worker" as he worked for the French navy.

The family's money ran out, as did their jewelry, which had been proffered as bribes to Germans conducting manhunts. "We were hungry and skinny, and looked everywhere for food," relates Gad. "Mother sent me to the market dressed as a local in the hope that I would be able to obtain food. We would go to the field next to the house and gather mallow, which became our staple diet. We scavenged for food in the bakery's garbage bins, and I brought home soiled flour. We sifted it and made a ‘meal.'"

After the German retreat from Tunisia in May 1943, a man with a bushy beard and non-Jewish garb came to the door. At first, Gad didn't recognize him, but it was his father. Gad took him to his older brothers, who also didn't recognize their father.

Reunited, the family returned to Nabeul, where they celebrated Gad's barmitzvah. Afterwards, they moved to Tunis, where Gad joined the Hashomer Hatzair youth movement and became an active member. He sailed to France and learned Hebrew at a hachshara (pioneer training) farm.

In March 1948, Gad immigrated to Eretz Israel (Mandatory Palestine) on an Italian fishing boat. He joined Kibbutz Beit Zera and enlisted in the Palmach. Later, he was one of the founders of Kibbutz Karmia, before eventually settling in Ashkelon. An amateur photographer, Gad later turned his hobby into a profession.

Gad and Mona z"l have four children, thirteen grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren. As Gad puts it:

"That is my revenge for the suffering caused by the Nazis."

Rachel Katz

Rachel Katz née Laufman was born in 1937 in Antwerp, Belgium, to an immigrant family, the second of four children. Her parents, Feyge-Tzipora and Benjamin, had emigrated from Bukovina, Romania. Feyge was a seamstress, and Benjamin earned a living as a merchant and glazier.

The Germans occupied Belgium in May 1940. In June 1942, Benjamin was arrested and sent to a forced labor camp in France. From there, he was transferred to the Mechelen transit camp in Belgium and then deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where he was murdered in November 1942.

Feyge was left to ensure the survival and welfare of her four small children, the eldest of whom was just seven years old. They moved from one hiding place to another, and Maria Lubben, a neighbor in one such hiding place, obtained forged papers for them and helped them with shopping for essentials, as they were frightened to leave their apartment. When the German manhunts intensified, Lubben moved Rachel and her siblings to her own home, and later, she found a hiding place for Rachel and two of her siblings in a convent near Antwerp. Lubben was eventually recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations.

After several months, Rachel and her siblings were removed from the convent due to the impending threat of a Gestapo raid. They returned to Antwerp and lived in hiding with their mother under assumed identities with the assistance of the Belgian underground, until Belgium was liberated in September 1944.

After the war, Rachel attended the Tachkemoni school, also working to help support her family. She immigrated to Israel in 1957, got married and began raising a family.

In 2000, Rachel joined the YESH Holocaust Children Survivors in Israel association. She quickly became very active and was given responsibility over branches throughout Israel. Today, she serves as the association's chairperson. She is also active in the Amcha association, which offers psychological and social support services to Holocaust survivors and their families. For many years, she traveled from her home in Ramat Gan to take care of Holocaust survivors at the Sha'ar Menashe Hospital, where she gave them emotional and material support, and advocated for them.

Rachel also maintained close contact with survivors outside of her work with YESH and Amcha, and thanks to the connections she made with philanthropists, she was able to collect donations on their behalf. She went to the press and approached local authorities and public figures, including Members of Knesset, in her battle to improve their welfare.

Rachel helped many survivors to clarify and access their legal rights, including allowances, discounts on services and special benefits. She advocates for Holocaust survivors from North Africa and is active in the endeavor to increase their benefits. She is dedicated to the cause of improving the circumstances of Holocaust survivors and is personally involved in their welfare on a daily basis.

Rachel and Shmuel have two children, three grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Arie Reiter

Arie Reiter was born in the town of Vaslui, Romania, in 1929, the firstborn son in an Orthodox, Hasidic family of five. His parents, Lazer (Eliezer) and Tova Bella, owned a restaurant and a small inn. Arie attended the Aseh Tov Jewish school and the local Talmud Torah (Orthodox Jewish elementary school).

In 1940, the antisemitic Romanian regime shut down Arie's school. His family was dispossessed of the inn and had to move into a wooden warehouse. Lazer was sent to a Romanian forced labor camp, where he died in 1943. Arie and his younger brothers, Binyamin and Moshe, worked in stores to support themselves and their mother, and frequently went hungry.

In January 1944, Arie was sent along with dozens of other children to a labor camp near the town of Runcu, Romania, where he was put to work paving a road in the forest and constructing a wooden bridge over the river, which exists to this day. Cold and starving, he slept on a wooden bunk in an abandoned cowshed. The children were expected to meet a daily labor quota, and those who didn't succeed were brutally flogged. Arie's friends sometimes took pity on him and gave him a slice of bread from their meager rations.

The Red Army reached the area in August 1944 and liberated the camp. Arie walked the 80 kilometers back to Vaslui barefoot, while Soviet planes strafed overhead. He weighed 30 kilograms on his return to the town. Reunited with his family, they lived together in the cellar of a relative's home, as their house had been destroyed in the bombing.

Arie graduated from the Trade and Economics School. He joined the Bnei Akiva youth movement, becoming head of the Vaslui branch, collected money for the Jewish National Fund, and was active in the Youth Aliyah. In 1947, he sent his two brothers to Eretz Israel (Mandatory Palestine) on the Ma'apilim (illegal immigrants) ship Pan York, but he remained in Romania to assist with the immigration campaign, as per the request of the Zionist leadership. Arie immigrated to Israel in 1951, where he was reunited with his mother and brothers in Be'er Sheva.

Arie worked in the Finance Ministry and then for Mizrahi bank. Rising through the ranks, he eventually became the bank's deputy director. At the same time, he gained both bachelor's and master's degrees in Jewish history.

Arie served as a member of the religious council in Be'er Sheva, treasurer of the Negev museum, and city councilman. He assisted in the establishment of the Bnei Akiva yeshiva (Talmudical college) Ohel Shlomo in Be'er Sheva and the Naot Avraham high school in Arad. One of the founders of the Struma synagogue, he has served as its beadle for over sixty years. In an effort to increase awareness of the Ha'apala (illegal immigration) movement among today's youth, he established the Struma Museum, visited annually by dozens of groups of IDF soldiers and youth. In 2002, Arie was given the Yakir Ha'ir (honored citizen) award, in recognition of his wide-ranging community service in Be'er Sheva.

Arie and Yehudit have five children, and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

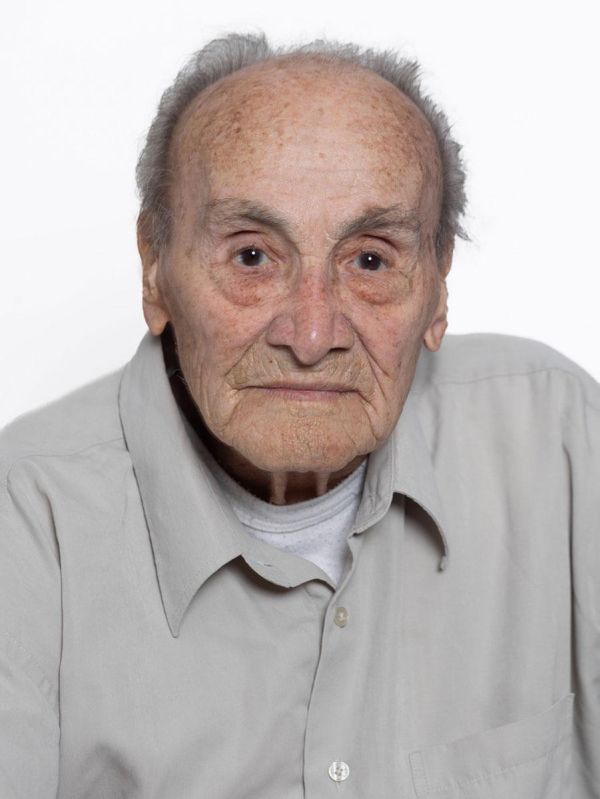

Felix Sorin

Felix Sorin was born in 1932 in the city of Mogilev, Byelorussia, to Frida and Natan, the youngest of their three children. Natan was a tailor by trade and a communist activist, but despite his political leanings, the family spoke Yiddish at home and observed the Jewish holidays.

In 1939, the Soviets entered Eastern Poland. Natan was sent to Oszmiana for work, so the family moved there with him.

When the Germans invaded the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941, the Sorins fled eastward. In the ensuing chaos, Felix was separated from his family and was left alone in German-occupied territory, where a stranger advised him not to reveal his Jewish identity or his father's communist activism.

Felix roamed from place to place until he reached Minsk, where he was incarcerated in the ghetto and witnessed the murder of Jews. He escaped, and upon arrest, passed himself off as a Russian orphan and was sent to an orphanage. Several months later, he was suspected of being Jewish and was sent to Minsk to stand before a committee. At the hearing, he insisted that he wasn't Jewish, his claim corroborated by the fact that he was uncircumcised. Committee member Vasily Orlov supported his case, and the committee secretary, who knew Felix, did not expose his true identity. After the war, Orlov was recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations.

Felix was returned to the orphanage and did not reveal his identity until the Red Army liberated the region in the summer of 1944. In the last months of the occupation, the Germans evacuated young boys to Germany for forced labor, but Felix escaped from the orphanage and evaded deportation.

After liberation, Felix feared that no one in his family had survived. The director of the orphanage suggested that he register as a Russian, but he insisted on registering as a Jew, stating that this was his real identity. He also hoped that this would help his parents locate him, should they still be alive. He was advised by the orphanage to contact the authorities for assistance in finding his parents, and in this way, he received notification that his father was alive and serving in the Red Army.

One day, Felix's older brother Isaak appeared at the orphanage, with the glad tidings that their parents had succeeded in fleeing eastward and survived. Isaak and their father Natan had both fought in the ranks of the Red Army, and Frida and Felix's older sister Roza had managed to stay alive in the Soviet Union. Isaak took Felix with him, and the brothers were reunited with their parents in Moldova.

Felix studied at the Odessa Polytechnic and became a researcher and lecturer.

In 1992, Felix and his family immigrated to Israel. He often meets youth, students and educators, tells his story at Yad Vashem, and is active in survivor organizations. Felix and Ida z"l have two children, five grandchildren, and five great-grandchildren.

Life in Israel Articles

Life in Israel Articles